For profit, obviously. Divesting from fossil fuel would lose business and lower profits, so the thinking goes. But is this true? A study finds ethical banks are just as profitable as major banks. If a mainstream bank adopts sustainable banking principles can they realistically expect to maintain profits? I look into the study’s methodology and see what a major bank can take away from the findings.

For profit, obviously. Divesting from fossil fuel would lose business and lower profits, so the thinking goes. But is this true? A study finds ethical banks are just as profitable as major banks. If a mainstream bank adopts sustainable banking principles can they realistically expect to maintain profits? I look into the study’s methodology and see what a major bank can take away from the findings.

The report “The Power of Sustainability-Focused Banking 2015” (PDF) was prepared by the not-for-profit Global Alliance for Banking on Values. It compares the financial performances of 25 ethical banks to 30 major banks in the world over a ten year period from 2004 to 2014. The group of major banks—including Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan Chase, Bank of China, HSBC—are the largest and systemically important financial institutions in the world. The group of ethical banks—including from Canada Vancity, Affinity Credit Union, and Assiniboine Credit Union—are banks guided by the Triple Bottom Line approach on people, planet, and profit, maintain a high degree of transparency in their governance and reporting, and other principles of sustainable banking.

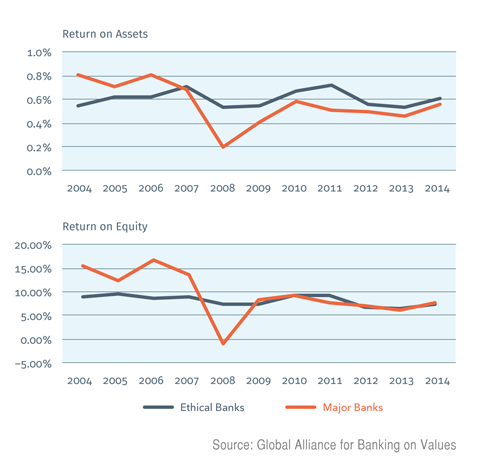

The study finds ethical banks are just as profitable as major banks. In the two main metrics used, the ten year average return on assets (RoA) of the ethical banks was 0.63% per year, beating the major banks’ 0.52% per year. For the return on equity (RoE), the ethical banks’ average was 8.4% per year, losing slightly to the major banks’ 8.9% per year. The report also finds the ethical banks’ performances are less volatile. The major banks had higher returns in the run-up to 2008 but suffered greatly during the stock market crash while the ethical banks sailed through 2008 unharmed.

So these findings show ethical banks have comparable profits to major banks. Should major banks adopt these sustainability principles then? We know Triple Bottom Line banking brings good to people and planet, and that may be good enough reasons for some to pursue it. But will it also bring good profits? If a mainstream bank were to adopt the sustainability banking principles as cited in the report—e.g. be radically transparent, actively use finance to do good, assist their clients to become more sustainable—could they realistically expect to maintain profits and returns to shareholders? I take a look at the study’s methodology to see if the findings are fair and reasonable.

Are the study’s metrics chosen fairly or cherry picked? According to “How to measure bank performance” (PDF) by European Central Bank, return on equity is the most common metric for bank performance. The limitation of RoE is that it’s not risk sensitive. Given the ethical banks’ RoE are similar to the major banks’ while being less volatile, this bodes well for the ethical banks. Other metrics often used by academics include return on assets (which is the other main metric used in the report), cost to income ratio, economic value added, risk adjusted return on capital, total share return, price-earnings ratio, and price-to-book value. So it seems the two metrics used are chosen fairly. In fact, the performance of the ethical banks might look even better if the report compares risk-adjusted returns since the ethical banks’ performances were less volatile.

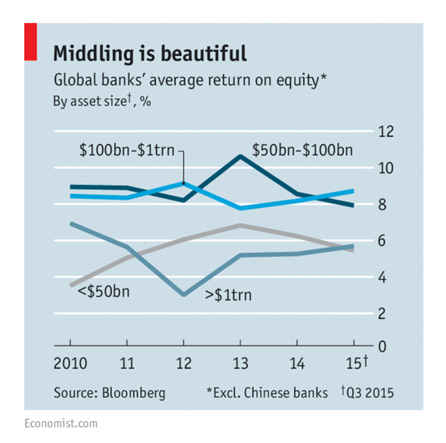

What about the size difference? The ethical banks in the study are all small. Can they compete with the big banks? How does the size of a bank affect its profitability? I found a recent analysis by The Economist comparing RoE of banks of different sizes. The results are surprising: among small, mid, and large size banks, the mid-size ones are actually the most profitable. The average RoE of mid-size banks (assets between USD$50 billion and $1 trillion) was the highest at 9%. This compares to the RoE of small banks (assets less than $50 billion) at 6% and large banks (assets more than $1 trillion) at 5%. The Economist finds economy-of-scale only works up to a certain point. Beyond that the benefits are minimal. Once a bank grows beyond a certain size and deemed to be systemically important, the extra regulatory restrictions imposed can substantially increase the costs of doing business. (See Big Banks Chop Chop, The Economist.)

The ethical banks in the study have $4 billion of assets on average (i.e. very small) while the group of major banks has approximately $1.5 trillion on average (i.e. large). Putting these two groups into the Economist’s analysis would suggest they both have comparable RoE based on their sizes. Therefore it doesn’t seem the ethical banks in the study have a size advantage or disadvantage over the major banks.

Do sustainability banking principles apply equally well to commercial banking and investment banking? The ethical banks in the study are primarily commercial banks whereas the major banks in the study are a mix of commercial and investment banks. How does this affect their profitability comparison? Do investment banks bring in high profits from services like mergers and acquisitions, derivatives trading, and other complex financial products?

Contrary to common belief, investment banking is actually less profitable. A 2014 study by the Bank for International Settlements, a global forum for central banks, found between 2005 and 2013 the average RoE for investment banks are 8%, below the all-banks average of 10%. Could this have driven down the RoE figures for the major banks in the study slightly? Possibly. Beyond this I did not find any further information. Until more investment banks adopt the sustainability banking principles, we do not know how it applies to investment banking and affects profitability.

Summing up, the two groups of banks in the study do have differences in size and business model in addition to their approach to sustainability. So it’s not a straight forward apple-to-apple comparison. But I didn’t detect any bias and I think the conclusion is reasonable and fair. From the data available, triple-bottom-line banking does not lead to reduced profit.

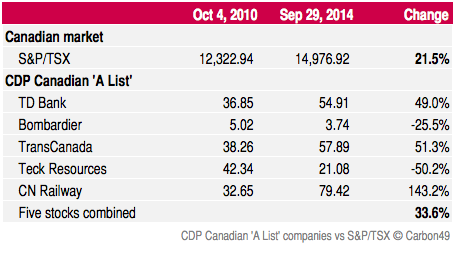

But how is this possible? The last time I looked into sustainable business and shareholder return, I found the greenest companies consistently outperform markets. To quote: “Time and again, in Canada and worldwide, companies that do the most in combating climate change have delivered financial returns that outperformed the markets. Fund managers and investors take note. The notion that progressive green companies must give up returns for environmental good is just plain wrong. It’s wrong when we look at the global market in the last four years: green leaders outperformed the market by 9.6%. It’s wrong when we looked at it from 2005 to 2011: green leaders delivered twice the financial return. It’s wrong in the Canadian market in the last four years: green leaders outperformed the market by 56%.” (See: The Greenest Companies Consistently Outperform Markets)

How could green companies devoting resources to fight climate change deliver better financial returns than non-green ones? Is it because they use their sustainability information to make better decisions to cut costs and manage risks? Is it because their more engaged employees drastically lower turnover rate and brought big savings? (See: LoyaltyOne lower staff turnover rate by 12% and Employee Engagement Drives Sustainability Strategy.) I don’t know why. I don’t know the exact causal links. Other studies (e.g. Waddock, Orlitzky, Schmidt, Rynes) have also found that a company’s social performance and financial performance are correlated. Whatever the reasons, being green and sustainable has not led to reduced corporate profits. In some cases, profits go up. Sometimes way up.

[…] article was originally published on Carbon49 ______________ Derek Wong is a recognized expert at ShareGreen by Walmart, panel judge for Earth […]

[…] Triple Bottom Line GABV Proves There’s Profit & Positive Impact In Sustainability-focused Banking Why Do Banks Invest in Big Oil? […]